There are no comments on this post yet

From Rust to Remarkable: How Restored Ships Become Floating Museums 🌊⚓️

🌊✨ Some ships are simply too important (culturally, technically, or emotionally) to be broken up for scrap. Across the world, conservation teams, naval architects and museum curators breathe new life into these vessels, transforming corroded hulls and tired decks into immersive time capsules. The result is more than a shiny hull: restored ships become floating museums where visitors can walk through history, feel the grain of an old spar, and imagine the lives of sailors who once called these vessels home.

Below are five striking examples of ship restoration that turned working vessels into public museums – with the year each ship was built and where you can visit them today.

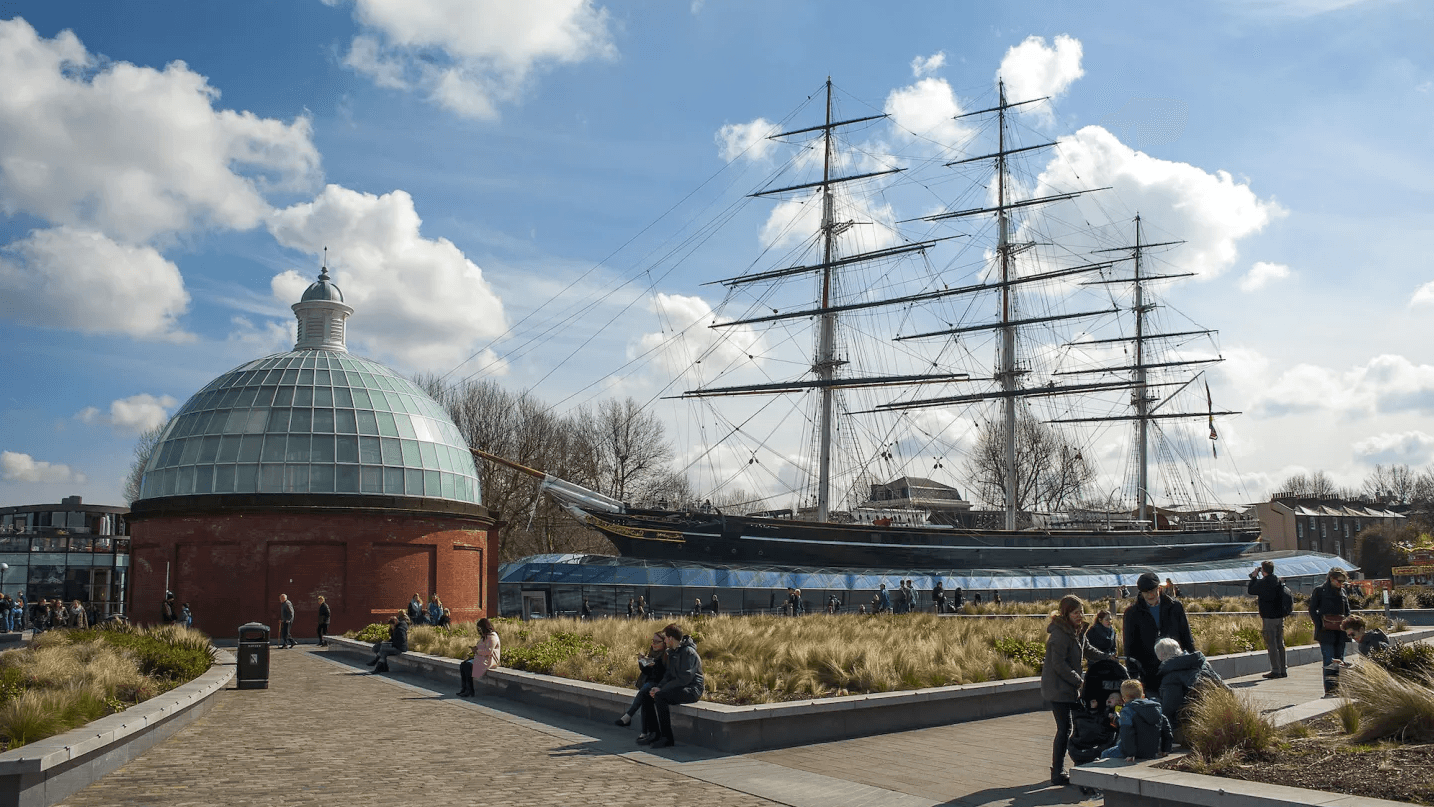

Cutty Sark. 1869, Greenwich, London (UK)

A celebrated tea clipper launched in 1869, the Cutty Sark is one of the last and fastest of her kind. After decades of commercial service and later decline, she was conserved and placed in a specially built dry dock in Greenwich, where visitors can now walk around and under her hull to appreciate the wooden craftsmanship and sleek lines that made her famous. The ship has undergone multiple major conservation efforts to stabilise and conserve both its iron frame and wooden planking, preserving the original fabric while making the site safe and accessible for the public.

USS Intrepid (CV-11). 1943, New York City (USA)

The aircraft carrier USS Intrepid, commissioned in 1943, survived intense action in World War II and later served in the Cold War and as a NASA recovery vessel. Saved from scrapping, Intrepid became the core of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York. Conservators faced challenges common to large steel warships: corrosion control, maintenance of flight-deck structures, and adapting cramped interiors for safe public access without destroying historical features. Today the carrier displays aircraft, exhibits about naval aviation and space history, and hosts educational programmes that connect visitors with 20th-century military and technological history.

Vasa. 1628, Stockholm (Sweden)

Perhaps the most dramatic rescue story belongs to Vasa, a Swedish warship that sank on her maiden voyage in 1628 and lay on Stockholm’s seabed for over 300 years. Salvaged in 1961 with large parts of the hull remarkably intact, Vasa is now the centrepiece of the purpose-built Vasa Museum. The conservation work on Vasa was—and remains—an ongoing scientific effort: desalination of timber, chemical treatments to stabilise centuries-old oak, and controlled climate conditions inside the museum to slow deterioration. Vasa is a prime example of how archaeology, conservation science and museum design work together to keep a fragile ship accessible to millions of visitors.

SS Great Britain. 1843, Bristol (England, UK)

Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s SS Great Britain, launched in 1843, was revolutionary as the first large iron-hulled, propeller-driven passenger ship. After a long and varied service life (and a period as a hulk in the Falklands) she was salvaged and brought back to Bristol, where an ambitious restoration returned her to a dock and built a museum around her. The project required careful stabilization of iron structure, recreation of historic interiors, and interpretive exhibits that explain Brunel’s innovations. The SS Great Britain shows how engineering heritage can be presented in a way that is both technically faithful and visitor-friendly.

Cruiser Aurora. Built 1897–1900, St. Petersburg (Russia)

The Russian cruiser Aurora, completed around 1900, has enormous symbolic value and has been preserved as a museum ship in St. Petersburg. Over the decades she has undergone periods of repair, refit and major restoration (including hull work and replacement of worn elements) to maintain structural integrity and her historic appearance. Ships like Aurora highlight the particular conservation demands of early steel warships and the cultural importance that drives governments and communities to maintain them as public monuments.

Why restoration matters – and what it costs us in care

Restoring a ship is rarely about returning it to "like new." It’s about choosing which parts of a vessel best tell its story, stabilising fragile materials, and making sometimes-compromised compromises between conservation and public access. Projects can involve: painstaking corrosion removal and cathodic protection for steel hulls; desalination and polyethylene glycol (PEG) treatment for waterlogged timber; custom dry docks and supporting structures; and interpretive & climate-controlled museum environments to protect the object for generations. These technical interventions are expensive and require long-term maintenance plans, but they let the public step into real, tangible history rather than a recreated set.

In short – floating museums keep stories afloat 🛳️✨

When a ship is rescued from scrap and reborn as a museum, it becomes a layered object: an engineering feat, a historical document, and a classroom in steel and timber. Visitors don’t just read about voyages – they walk the decks, touch the rail, and imagine the creak of timbers in a storm. That direct encounter is why communities invest in restoration: to preserve memory, teach craft and seamanship, and keep maritime heritage alive for future explorers.

Picture: Royal Museums Greenwich